Distinguishing mood changes between clinically significant degrees of depression and those occurring "normally" remains problematic. Depressive symptoms are best thought of as occurring in gradients of severity (Lewinsohn et al., 2000). In addition to intensity and severity, the identification of depression should also take into account the possible presence of other diseases and symptoms, as well as the degree of functional and social impairment. Although it is difficult to see a clear transition between "clinically significant" and "normal" degrees of depression, or even absence, it can still be said that the greater the severity of depression, the greater the burden of consequences (Lewinsohn et al., 2000; Kessing, 2007). When all aspects are considered, such as duration, degree and phase, history of treatment, group of symptoms, it is clear that there are significant problems when trying to categorize depressions into subtypes.

Common symptoms

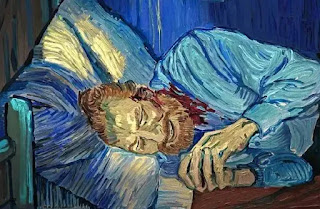

Prominent symptoms are therefore bad mood, sadness, anhedonia, pessimism, tearfulness, lethargy, poor concentration, frequent feelings of guilt, and even thoughts of self-harm. Common accompanying symptoms are anxiety, intrusive thoughts and rumination, fatigue, reduced daily activities, heart problems, agitation, insomnia, decreased appetite, weight loss, tension, and worsening of pre-existing pain. Although the list goes on, each patient has a different pattern of symptoms with varying intensity, propensity and uncertainty of consequences (NICE, 2010).The mood is often unresponsive to circumstances and remain gloomy throughout the day. It is also common for someone to wake up with a depressed mood that improves with the day, only to return to the original gloomy mood the next morning. For others, the mood may be reactive to positive experiences and events, but does not dwell there. At that high mood, low feelings lead back to a depressed state, often quickly (Andrews & Jenkins, 1999).

Behavioral and physical symptoms typically include tearfulness, irritability, social withdrawal, worsening (if any) of pre-existing pain, as well as secondary pain from muscle tension (Gerber et al., 1992), lack of libido, fatigue, and decreased activity; although agitation is common and visible anxiety frequent. Usually sleep is shortened and appetite is reduced (sometimes leading to significant weight loss), although for some people the reverse is the case. Interest and enjoyment in everyday life is lost, feelings of guilt, worthlessness and that every punishment is deserved are common. Self-esteem and self-confidence decrease, frequent feelings of helplessness, self-harming ideas and attempts or, unfortunately, the final outcome. Cognitive changes include poor concentration and attention, pessimistic and repetitive negative thoughts about self, past and future, mental slowing and rumination (Cassano & Fava, 2002).

Clinical depression and accompanying problems

Depression is often threatened by anxiety, whereby we can distinguish clinical conditions: only anxiety, depression with/without anxiety, or depression and anxiety separately below the threshold of recognition, but together in accordance with the context of the symptoms so that they form a clinical picture. In addition, the presentation of depression may differ by age, with young people showing more behavioral symptoms and older people with more somatic symptoms and fewer indications of low mood (Serby & Yu, 2003 👀).Some patients have a severe and typical presentation, including marked physical slowness (or marked agitation), complete lack of mood reactivity to positive events, and a range of somatic symptoms. This affects appetite and weight loss, reduced sleep with the usual pattern of waking up early in the morning and trying unsuccessfully to get back to sleep. Also, the pattern that the symptoms are most intense in the morning (daily variation) is repeated. This clinical picture is referred to in DSM-IV as depression with melancholic features, and in ICD-10 as depressive episodes with somatic symptoms. Of course, depression with an atypical picture is also characterized - reactive mood, increased appetite, weight gain and longer sleep, along with increased sensitivity to rejection (Quitkin et al., 1991).

People with more severe depression may also develop psychotic symptoms (hallucinations and/or delusions), most often thematically consistent with the negative, self-blaming thoughts and low mood commonly encountered in clinical depression, although others may develop psychotic symptoms unrelated to mood (Andrews & Jenkins, 1999). In the latter case, these mood-uncontrolled psychotic symptoms are difficult to distinguish from those of other psychoses, such as schizophrenia.

Reference

– Andrews, G. & Jenkins, R. (eds) (1999) Management of Mental Disorders (UK edn, vol. 1). Sydney: WHO Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and Substance Misuse.

– Cassano, P. & Fava, M. (2002) Depression and public health: an overview. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 849–857.

– Gerber, P. D., Barrett, J. E., Barrett, J. A., et al. (1992) The relationship of presenting physical complaints to depressive symptoms in primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 7, 170–173.

– Kessing, L. V. (2007) Epidemiology of subtypes of depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 115 (Suppl. 433), 85–89.

– Lewinsohn, P. M., Solomon, A., Seeley, J. R., et al. (2000) Clinical implications of ‘sub-threshold’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 345–351.

– NICE, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) (2010). Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition). Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society. PMID: 22132433.

– Quitkin, F. M., Harrison, W., Stewart, J. W., et al. (1991) Response to phenelzine and imipramine in placebo non-responders with atypical depression. A new application of the crossover design. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 319–323.

– Serby, M. & Yu, M. (2003) Overview: depression in the elderly. Mount Sinai Journalof Medicine, 70, 38–44.

Comments

Post a Comment